Article: Jinpa Means Generosity

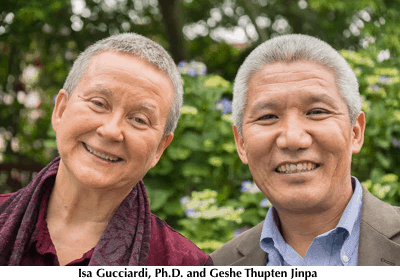

By Isa Gucciardi, Ph.D.

Editors’ Note: Geshe Thupten Jinpa has been His Holiness, the Dalai Lama’s principal English language interpreter and translator since 1987. A former Tibetan Buddhist monk, he holds a Ph.D. from Cambridge University. He is an adjunct professor of religious studies at McGill University and chairman of the Mind and Life Institute. He is well known in Tibetan Buddhist circles; several monasteries recognized him as an incarnation of one of their great teachers, but Jinpa (as he likes to be called) never took on the mantle of tulku, or incarnation lama. He is famous for his achievements in the complex form of debate that is the core form of scholarship in Tibetan Buddhist education.

Summary: A personal account of the impact of Geshe Thupten Jinpa’s work, presence, and generosity of spirit.

The morning after Jinpa left, the Tibetan Buddhist monks of the Gaden Shartse Dohkang who had been staying with us for several months were sitting around our breakfast table with us as they did each morning. But this morning, we were all a bit shell-shocked. As we sat together, we all felt that we were sitting still in the presence of Jinpa.

We drank our tea, and I tried to eat the lovingly prepared, cold, very fried eggs. But none of us really had much of an appetite. We were all trying to digest our good fortune at having just spent forty-eight hours of completely unstructured time with Thupten Jinpa. Jinpa, as he prefers to be called, is a scholar renowned throughout the Tibetan Buddhist community. In spite of his fame, Jinpa is humble, attentive, and soft spoken.

Jinpa had come to San Francisco from his home in Montreal to visit the monks, whose home was in South India. They were meeting in the middle. I tried not to make any jokes about the middle way when we realized where they were meeting. The monks were at the end of a yearlong tour across the United States that we had directed at the request of Jinpa. During the tour, they had visited college campuses, churches, temples, private homes, and retreat centers, sharing the wisdom of their Buddhist tradition as they raised funds for their new prayer hall and dormitories.

The monks in particular understood the gift we had been given by having Jinpa with us in such in an intimate setting. The gift was the presence of Jinpa. He had spent hours and hours with us over the last few days, talking and laughing – moving seamlessly from Tibetan to English and back – including us all in a conversation that seemed to be taking place in just one language through his skillful interpreting.

Up until this time, as adults the monks had only been able to chat with him or sit with him for brief amounts of time in ceremonies or in teachings. His duties as His Holiness’ interpreter took him far and wide from the monastery – and his choice to step out of the monks’ robes had created a separation between them in every day life. But they had felt that gulf shrink as our days together had unfolded.

Jinpa and the monks spent a lot of time reminiscing about the days of their youth, growing up in South India after their parents had fled Tibet with the Chinese occupation of Tibet. They told stories about their old masters who cared for them and who taught them in the monastery while their parents worked on the road crews for the Indian government. These monks, Geshe Gyaltsen, Geshe Thinlay, and Geshe Donye, had roomed with Jinpa as young monks at the monastery. They had watched him as he grew into the promise of his brilliance as a great debater and as he stepped into his duties as the principle English language interpreter of His Holiness the Dalai Lama. Through all these changes that took Jinpa away from them, their love for him remained steady. They were so happy to have had the last few days of meeting with him, a world away from their adventures as young scholars.

My own love for Jinpa arose first from a place within me I could not really name at the time. Like most Westerners, I first encountered Jinpa when he was interpreting for His Holiness. At the time I was working as a professional interpreter, so I knew his craft well even though I worked in different languages.

I remembered how dumbfounded I was when I first heard him start the interpretation of His Holiness’ words. I understood deeply, and all at once, and not at all how fully and completely he was conveying not only His Holiness’ words, but also his intentionality. He was carrying the transmission of truth expressed at a subtle level across the divide of language perfectly, so that we were all receiving that transmission from His Holiness along with the meaning of his words.

As an interpreter I had always done my best to bridge the gulf of misunderstanding or lack of understanding that existed between two people or a group of people for whom I was interpreting. I had always taken my charge as that bridge very seriously and dedicated myself completely to the craft of translation. My love for words, which, when I was young did not hold the depth of understanding about the nature of words that I attained as I grew older, always sustained me. I had always found meaning in my efforts to create bridges between people.

Even though I could not speak Tibetan, I knew I had met a master bridge maker as Jinpa continued to interpret, hour after hour, with very little break. I was stunned and awed by what I could perceive of his offering to us, and overwhelmed by what I could not perceive as I experienced Jinpa moving effortlessly in the mastery of his craft. He was bringing this ancient wisdom across into the modern time even as he brought the meaning of the words from a language so far from English into effortless, beautifully phrased English. And all the while, he was bridging the Tibetan mindscape, which is so different than our own here in the West. He was bridging so many things at once that I was dizzy, and he was doing it all so effortlessly and beautifully that I was overcome. There was nothing to do but cry. And I cried for all four days of those teachings, as deeper and deeper levels of understanding about what Jinpa was doing with those words dawned on me.

As we were sitting around the table that morning, we all offered our first memory of Jinpa. There were long gaps of silence between each person’s recounting of their first memory of Jinpa. Geshe Gyaltsen talked about wrestling with him when they were boys and he talked about the way in which their old master would pull their ears when they did not have a teaching mastered correctly.

Geshe Donye in his ineffable, quiet way, and in just a few words, expressed affection for Jinpa that I could feel radiating throughout his being. He spoke of the times they rode the monastery’s tractor together as they were working in the fields of the Tibetan settlement. He talked about their shared excitement when that tractor arrived. The tractor was a miracle, and they delighted in it together. They had all been clearing the jungle by hand that the Indian government had offered the Tibetans after they had lost their homeland to the Chinese. They had to clear acres and acres of land to make a space to rebuild their monastery and create the simple makeshift houses that made up the Tibetan settlement in those early days.

Geshe Thinlay described his awe in the debate hall as Jinpa emerged from the group of monks in his class as the champion at the debate competitions that were held annually between all the major monasteries. The role of debate is central to the education of the academic monastic universities and debate champions are recognized as erudite and masterful scholars. There is no higher honor than to be named debate champion.

Geshes Gyaltsen, Dhonye, Thinlay and Jinpa were part of the same house, the Dokhang, at the Gaden Shartse monastery. They had all grown up in exile. When Jinpa was very young, he came with his parents across the high snows of Tibet, through the Himalayas to India to escape Chinese oppression. As we sat around the table, he told stories about the prison that was their first stop in India. It was filled with flies and bugs of all types, and heat, and disease. He recounted stories of how many loved ones had died in that place. They all recalled the hardships of the long trip south to the jungle where they worked so hard to create a new life, and where they learned the dharma together.

When my turn came to speak, I tried to express my experience of being taught something deep and ineffable just from Jinpa’s presence. I tried to explain that I felt us all receiving wave after wave of clarity and purpose just from his presence. Jinpa means generosity in Tibetan. It is one of the Six Perfections that also include joyful perseverance, patience, wisdom, ethical discipline, and concentration. The development of these qualities is an essential task of the developing Bodhisattva – a being in Mahayana Buddhism who seeks to help other beings step out of suffering. These are also the essence of an enlightened state of being.

Until I had met Jinpa, my understanding of the word generosity had become a bit intellectual. As a child, I could feel my own generous nature rising up in me more easily. But as an adult, I found it rising less easily as I found it best to hold it back in order to avoid the pain of having it rebuffed or misunderstood by those around me.

Jinpa’s grace of being had none of these twists and turns. His presence seemed to go into the places where the twists around giving and receiving existed within me and untwist them. His effortlessness in sharing of himself made it safe for me to share myself. Over the last few days, his open heart created a deep and wide space for each person to present themselves to him to be seen fully and thoroughly. When he looked into me, I felt him showing me the places where I could no longer open my heart the way he did.

When I felt the level of spaciousness that Jinpa created for me, as he created for everyone, I recognized that it was a spaciousness I had not afforded myself in a very long time. As I sat with him at that table, I could feel the rumbling of all the constriction and denial within me breaking open as the waves of spaciousness and generosity from Jinpa flowed into the parts of my being I had forgotten about – or perhaps which I had never known.

The day before, as we rested in Jinpa’s presence, I think we could all feel those waves that emanated from him as he was simply sipping tea. Each of us tried to express our experience in different ways, but, when words failed, we always just pointed to our love for Jinpa.

As we sat in the silence that followed each of our attempts at expressing our experience at the breakfast table that morning after Jinpa had left, those waves were still palpable. I found a new kind of kinship with the monks as we stopped struggling to express our experience in words. I felt that we understood what the other was trying to say by sharing our intention in silence. Every once in awhile, one of us would try to articulate again our experience of Jinpa’s generosity.

One of my efforts went something like this: In the West, when we speak about generosity, it generally has to do with money. We think about generosity having to do with the sharing of material goods. We think about generosity as a kind of duty that you engage in because you should, not because you necessarily want to. We talked about generosity being something that is not even really a value to aspire to in the West. People don’t see it as something to be treasured or cultivated, even when it comes to material goods.

The monks were surprised when they heard my thoughts about generosity in the West. Despite the fact that they had lived for so long with so much material deprivation, generosity as a value in relationship to material goods was a given for them. Spiritually, it was such a natural part of their lives – a natural spring of experience that arose within them.

This particular direction of discourse soon collapsed back into silence. Then Geshe Gyaltsen went and got a book in Tibetan that was wrapped in saffron cloth – the kind that has no binding, but is made up of individual pages of writing, held together by wood or stiff cardboard at the bottom and top of the stack of pages. He read the story of the Buddha, who was offered dirt by a young child who was playing in the dirt as he passed by. Dirt was the only thing he had to offer Buddha, and so he offered it. The official who was accompanying Buddha started to chase the child away, and Buddha said, “No – this child has offered me something of great value. He has offered me the only thing he has and he has offered it with joy and sincerity and kindness – so do not push him away, do not ask him to go. Let us stay here together.” As Geshe Gyaltsen read the story in Tibetan, all the monks nodded their heads. Then he kindly translated it for me. I knew the story, but I understood it in a new way.

As we moved into silence again, I was so grateful to the monks for being my teachers. I was so grateful to the monks for being my fellow students to a great master like Jinpa. I was so grateful that the path of my life had led me into contact with Jinpa, and I wished that all beings could experience him as we had over the last few days.

LIKE THIS ARTICLE? SIGN UP FOR FREE UPDATES!